Olympic Gold Medals Aren't Pure Gold: Material Worth $750

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The $1.47 Million Medal That Shocked the World

- The Ancient Olympics: When Winners Got Olive Wreaths, Not Gold

- The Birth of Modern Olympic Medals: 1896 Athens

- The Last Solid Gold Medals: Stockholm 1912

- Why the Olympics Stopped Using Pure Gold

- Current Medal Composition: The Sterling Silver Secret

- IOC Regulations: Official Medal Standards

- Material Value Breakdown: The $750 Reality

- Market Value vs Intrinsic Worth: The $40,000 Gap

- The Most Expensive Olympic Medals Ever Sold

- Cultural and Historical Factors Affecting Value

- Manufacturing Process: How Medals Are Made

- Paralympic Medals: Equal Composition, Unique Features

- Controversial Medal Sales: Athletes Who Sold

- Legal Status: Can Athletes Sell Their Medals?

- The Psychology of Medal Value: Why Symbolism Trumps Material

- Unique Medal Designs Through Olympic History

- Environmental Sustainability: Recycled Gold and Silver

- The Future of Olympic Medals: What’s Next?

- Conclusion: The True Value of Olympic Gold

- Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction: The $1.47 Million Medal That Shocked the World

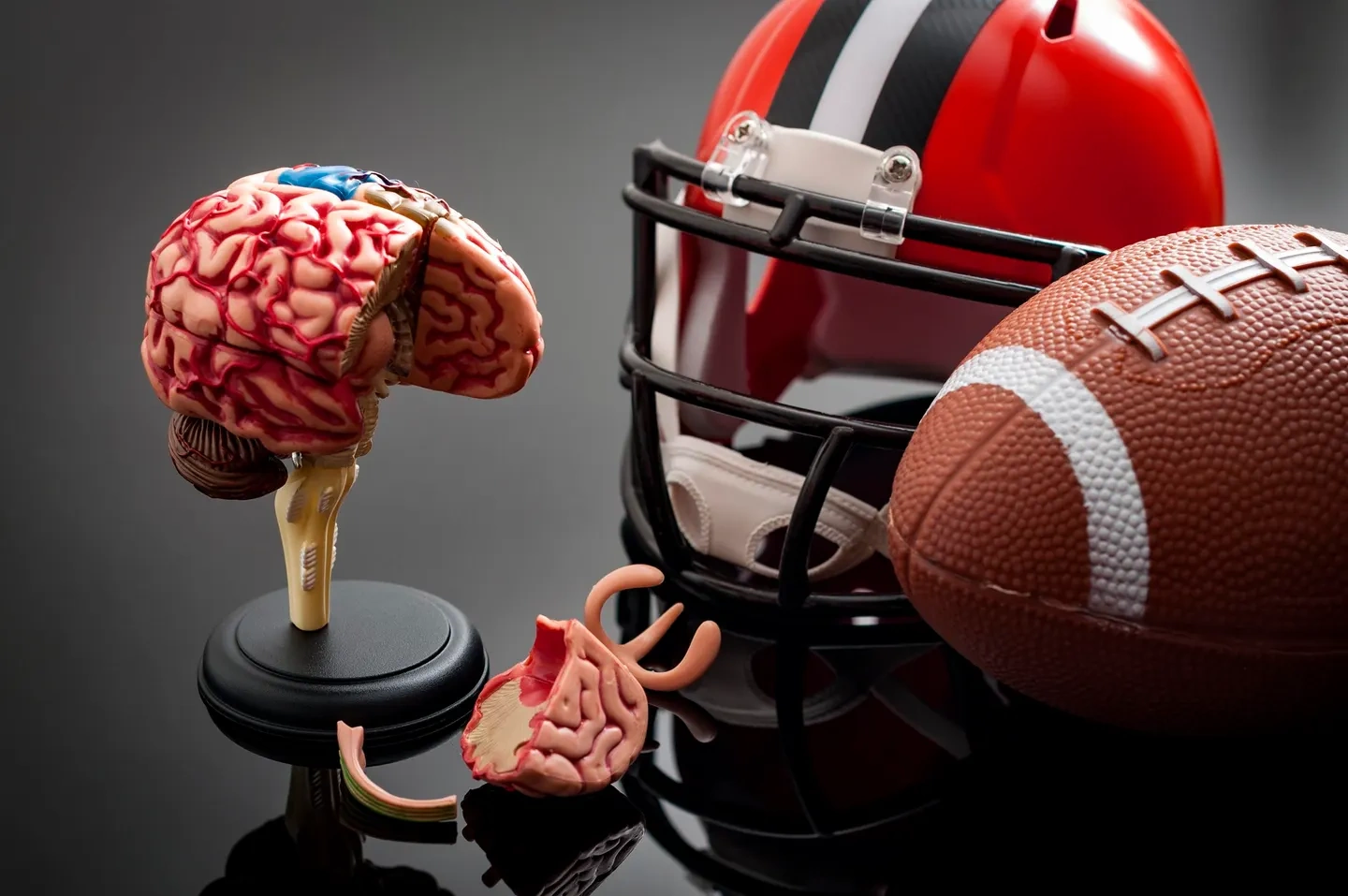

The hammer fell at SCP Auctions in December 2013 when an anonymous bidder paid one million four hundred sixty-six thousand five hundred seventy-four dollars for a single Olympic gold medal, shattering previous auction records and sending shockwaves through the sports memorabilia world that had never witnessed such astronomical pricing for what technically contained just twenty-five dollars worth of gold plating over seven hundred dollars of sterling silver creating material value under eight hundred dollars that paled against the final sale price representing nearly two thousand times the intrinsic metal worth. The medal belonged to Jesse Owens from the 1936 Berlin Olympics where the African American track and field legend won four gold medals in front of Adolf Hitler while dismantling Nazi theories of Aryan supremacy through athletic performances that transcended sport becoming powerful political and social statements that history remembers as among the most significant Olympic moments ever witnessed, with this particular medal’s extraordinary auction price reflecting not the precious metals it contained but rather the historical weight, cultural significance, and symbolic power that Olympic gold represents when combined with legendary athletic achievement and pivotal historical context.

The revelation that this seven-figure medal contained less than one thousand dollars of actual gold and silver shocked casual observers who assumed Olympic gold medals consisted of solid gold worth tens of thousands of dollars in raw materials alone, creating widespread public awakening to the reality that Olympic organizing committees have used gold-plated silver medals since 1912 rather than solid gold construction that economic practicality abandoned over century ago when expanding Games participation from several hundred athletes to thousands made pure gold medals financially unsustainable for host cities already spending billions on venues, infrastructure, and operational costs. The International Olympic Committee regulations establishing minimum precious metal standards that gold medals must contain at least six grams of gold plating over sterling silver base weighing minimum 550 grams creates official specifications that balance tradition, prestige, and economic reality through maintaining gold appearance and sufficient precious metal content to justify “gold medal” designation while avoiding prohibitive costs that solid gold would require.

The following explanatory video reveals the truth about Olympic medals; however, there is still information hidden within the exclusive details at the bottom of this article – insights you may not have discovered yet :

The cognitive dissonance between Olympic gold medals’ perceived value as ultimate sporting achievement symbol and actual material composition worth fraction of what most people imagine reflects broader disconnect between symbolic worth and intrinsic value that characterizes many culturally significant objects where meaning, history, and emotional resonance create valuations completely detached from physical material costs. The Olympic movement’s decision maintaining gold-plated medals rather than cheaper alternatives like bronze with gold finish or purely symbolic awards without precious metals demonstrates understanding that tradition and prestige require genuine gold and silver content even when economic efficiency might suggest otherwise, with minimum standards ensuring medals contain real value beyond purely symbolic tokens while pragmatic plating rather than solid gold allows Games sustainability that pure precious metal construction would threaten through escalating costs that smaller or developing nations hosting Olympics could not reasonably bear.

The journey from ancient Olympics where victors received olive wreaths and amphora filled with olive oil rather than precious metal medals through early modern Games awarding solid gold, silver, and bronze medals to current gold-plated silver standard that has persisted for over century reveals how Olympic traditions evolve through practical necessity while maintaining symbolic continuity that connects contemporary Games to their historical roots. The careful balance between honoring tradition through using precious metals and adapting to economic realities through pragmatic composition changes demonstrates International Olympic Committee’s institutional wisdom recognizing that symbolic power derives not from specific material compositions but from meaning, achievement, and cultural significance that Olympic medals represent regardless of whether they contain twenty-five grams of solid gold or six grams of gold plating over silver core.

The broader implications about value, worth, and significance that Olympic medal composition reveals extend beyond sports into fundamental questions about how societies assign importance to objects, achievements, and symbols with material value often proving completely disconnected from cultural, historical, or emotional worth that makes certain items priceless despite containing inexpensive materials. The Olympic gold medal as perfect case study in this phenomenon where eight hundred dollar material value transforms into million-dollar auction prices through accumulated meaning from representing ultimate athletic achievement, years of sacrifice and training, national pride, historical moments, and individual stories that imbue physical objects with significance that mere material composition cannot capture or explain fully.

Let’s examine the fascinating evolution of Olympic medals from ancient olive wreaths through solid gold medals to modern gold-plated silver standard, exploring why this change occurred, what current medals actually contain, how manufacturing processes create these iconic awards, what factors determine their market value so dramatically exceeding material worth, and most importantly what this reveals about how humanity assigns value to achievements and symbols that transcend mere physical composition through cultural significance that makes Olympic gold perhaps the most recognizable and coveted sporting prize in human history despite containing less gold than a typical wedding ring.

The Ancient Olympics: When Winners Got Olive Wreaths, Not Gold

The ancient Olympic Games, held in Olympia, Greece, from 776 BC to 393 AD, did not award victorious athletes medals of precious metals, but simple olive wreaths called koutinos, woven from the branches of the olive tree they revered in their beliefs near the Temple of Zeus., with this humble natural crown representing highest athletic honor in ancient Greek world despite containing zero monetary value demonstrating that symbolic significance rather than material worth characterized Olympic prizes from the Games’ earliest origins. The olive wreath tradition stemming from Greek mythology where Heracles supposedly planted the sacred olive tree and decreed its branches would crown Olympic victors created religious and cultural meaning that mere precious metals could not match in society where gods and heroes provided legitimacy and significance to human achievements through mythological connections that modern secular medals lack despite their gold and silver content.

Material Rewards Beyond the Wreath

The olive wreath as official Olympic prize came accompanied by substantial material rewards that individual city-states provided to their victorious athletes including cash payments often equivalent to several years’ wages, lifetime pensions for some champions, free meals at public expense for life, tax exemptions, front-row theater seats, and commissioned poetry and statues celebrating their achievements, with these practical benefits far exceeding any value that precious metal medals might have provided making the symbolic olive wreath combined with material hometown rewards creating complete prize package that recognized both symbolic achievement and practical financial reality. The amphora filled with olive oil from sacred groves that Panathenaic Games awarded alongside olive wreaths represented another form of valuable prize because high-quality olive oil functioned as currency in ancient Mediterranean world with large quantities having genuine economic value that winners could use for personal consumption or sell for significant sums supporting themselves and families for extended periods after competition.

The absence of gold, silver, or bronze medals in ancient Olympics reflected partly that precious metal medals as awards for sporting achievement didn’t exist as cultural practice in ancient world where wreaths from sacred plants, pottery vessels, and inscribed tablets served as typical competition prizes across various Greek athletic festivals, with Olympic olive wreath’s value deriving entirely from its sacred origin and cultural meaning rather than material composition that deliberately avoided monetary worth to emphasize spiritual and cultural significance over commercial value. The eventual Roman practice of awarding successful gladiators and athletes with palm branches and crowns similarly prioritized symbolic recognition over material value, though Roman culture increasingly included monetary prizes and valuable goods as athletic rewards reflecting society’s commercial orientation that Greek Olympic tradition resisted through maintaining simple olive wreath as supreme prize that meaning rather than material defined.

The Birth of Modern Olympic Medals: 1896 Athens

The first modern Olympic Games in 1896 Athens introduced medals as awards though not in the gold-silver-bronze system contemporary Olympics use, with winners receiving silver medals and olive branches while second-place finishers got bronze medals and laurel branches creating two-tier rather than three-tier award system that inaugural modern Games employed before establishing current format at 1904 St. Louis Olympics. The decision to award medals rather than following ancient tradition of olive wreaths alone reflected modern sensibilities about tangible awards and European sporting culture where medals had become standard prizes for various competitions including military honors, academic achievements, and sporting contests that nineteenth-century society regularly employed for recognizing excellence across multiple domains.

The 1896 Athens medals designed by French sculptor Jules-Clément Chaplain featured Greek goddess Nike representing victory on obverse side with Acropolis in background, while reverse depicted Zeus holding Nike in his hand alongside Greek inscription reading “Olympia” connecting modern Games to ancient heritage through classical imagery and mythological references that organizers deemed essential for legitimacy and cultural continuity. The silver medal composition using substantial precious metal content estimated at approximately 90-95% silver created awards with significant intrinsic value that cost organizers considerable sums though participating athlete numbers totaling just 241 from 14 nations competing in 43 events made precious metal medals economically feasible at scale that later Olympics’ thousands of athletes would make impractical for solid precious metal construction.

The introduction of gold medals as first-place awards occurred at 1904 St. Louis Olympics establishing the gold-silver-bronze hierarchy that has persisted for 120 years becoming so entrenched in sporting culture that “going for gold” and “gold medal performance” entered common language as metaphors for ultimate achievement and peak performance extending far beyond athletic contexts into business, academics, and general excellence recognition. The 1904 decision to create three-tier medal system reflected emerging understanding that recognizing top three finishers rather than just first and second place provided more athletes with tangible recognition and created more dramatic competition where bronze medal races often proved as exciting as gold medal contests, with third-place finishers receiving lasting recognition rather than leaving Games empty-handed despite world-class performances that narrow margins separated from medal positions.

Shop on AliExpress via link: wholesale-olympic-memorabilia-collectibles

The Last Solid Gold Medals: Stockholm 1912

The 1912 Stockholm Olympics awarded the last solid gold medals in Olympic history using approximately 24 grams of pure gold creating medals with intrinsic value around $1,500 at 2025 gold prices compared to modern gold-plated medals worth under $900 in raw materials, with this final year of solid gold reflecting both traditional commitment to precious metals and approaching economic limits where expanding athlete participation would make continuing solid gold financially unsustainable for future host cities. The Stockholm organizing committee’s decision to maintain solid gold despite increasing costs demonstrated Swedish commitment to Olympic prestige and tradition, though subsequent International Olympic Committee regulations would formalize the practical necessity of transitioning to gold-plated silver that 1912 represented final gasp of attempting to maintain before economic reality forced permanent change.

The 1912 medals designed by Swedish sculptor Bertram Mackennal featured modern design departing from classical Greek imagery that previous Olympics had employed, with reverse showing herald proclaiming Olympic Games alongside Swedish text creating culturally specific design that host nations would increasingly employ to reflect their identities rather than universal Olympic symbolism alone. The solid gold composition using approximately 24 grams represented substantial precious metal investment with 885 gold medals awarded across all sports creating total gold cost exceeding one million dollars in contemporary currency for metal alone before considering design, manufacturing, and presentation costs that complete medal production required.

The transition from solid gold to gold-plated silver occurring after 1912 reflected not sudden policy change but gradual recognition that Olympic growth from several hundred to several thousand athletes made solid precious metal medals economically impractical, with International Olympic Committee formalizing minimum standards that maintained gold and silver content while reducing costs through plating rather than solid gold construction. The 1920 Antwerp Olympics became first post-1912 Games to use gold-plated silver medals establishing standard that would persist for over century with only minor variations in plating thickness and base metal purity that different host cities employed while maintaining basic construction that economic necessity and IOC regulations both mandated.

Why the Olympics Stopped Using Pure Gold

The economic reality driving Olympic transition from solid gold to gold-plated silver medals stemmed from explosive growth in athlete participation that made maintaining solid precious metal awards financially unsustainable, with 1912 Stockholm Games awarding 885 medals to athletes from 28 nations while modern Summer Olympics distribute over 5,000 medals to participants from 200-plus nations creating scale increase where solid gold would cost approximately $50-75 million in materials alone before manufacturing and presentation expenses that host cities already spending billions on Olympic infrastructure and operations cannot justify for awards that gold-plated alternatives provide at fraction of cost.

The mathematical calculation shows that solid gold medals using 24 grams at $65 per gram gold price equals approximately $1,560 material cost per medal, multiplied by 1,700 gold medals that typical Summer Olympics awards creates $2.65 million total just for gold medals before considering silver and bronze, versus current gold-plated medals costing approximately $750 in materials representing $1.275 million for all gold medals creating savings of nearly $1.4 million that alone might not seem enormous for multi-billion dollar Olympic budgets but combined with other cost pressures and recognition that material composition doesn’t affect symbolic value makes gold-plating obvious choice that maintains tradition and prestige while avoiding unnecessary expense.

The democratization of Olympic participation expanding from elite European and North American athletes to global representation from all inhabited continents increased medal counts dramatically as new sports, events, and competing nations joined Olympics creating upward pressure on medal production that solid gold would make prohibitively expensive, with transition to gold-plated silver enabling Olympic expansion by reducing per-medal costs allowing host cities accommodating growth without corresponding precious metal expense increases that would otherwise create pressure to limit events or participation that Olympic ideals reject in favor of maximum inclusion and opportunity for athletes worldwide regardless of nationality, wealth, or geopolitical standing.

Current Medal Composition: The Sterling Silver Secret

The modern Olympic gold medal consists of sterling silver core weighing minimum 550 grams composed of 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper alloy providing durability and workability that pure silver’s excessive softness would lack, with this substantial silver base coated in minimum six grams of pure gold through electroplating process creating thin gold layer typically 6-8 micrometers thick that covers entire medal surface providing authentic gold appearance and precious metal content while avoiding solid gold’s prohibitive cost that economic necessity eliminated from Olympic medal production over century ago.

The silver core composition using sterling rather than pure silver reflects practical metallurgy where 925 silver provides superior strength, resistance to scratching and denting, and better long-term durability than pure silver’s softness would allow for medals that athletes handle, display, and potentially subject to wear over decades of ownership, with copper addition creating harder alloy without significantly affecting appearance or value while improving structural integrity that purely decorative awards might not require but sporting achievement symbols that athletes treasure for lifetimes benefit from through maintaining condition and appearance across years of handling and environmental exposure.

The gold plating application using electrochemical process deposits pure gold atoms onto silver surface through electrical current passing through gold salt solution with medal acting as cathode attracting positively charged gold ions that bond to silver creating uniform coating thickness controlled by current strength, duration, and solution concentration, with typical plating requiring several hours achieving specified thickness that IOC regulations mandate for official Olympic medals. The plating thickness of 6-8 micrometers equating to approximately 0.006-0.008 millimeters seems incredibly thin representing just fraction of human hair width yet proves sufficient for creating durable gold finish that resists wear under normal handling and display conditions that medals typically experience during ownership, with gold’s chemical stability and resistance to corrosion ensuring that plating maintains appearance and integrity for decades when properly cared for through avoiding harsh chemicals, excessive polishing, and environmental extremes that might accelerate deterioration.

The total medal weight of 556 grams mandated by current IOC regulations represents substantial mass creating impressive physical presence that befits ultimate sporting achievement designation, with diameter of 85 millimeters and thickness of 8-10 millimeters creating substantial disc that visual and tactile impact both contribute to medals’ prestige and ceremonial significance beyond mere material composition. The design flexibility that silver core allows enables intricate bas-relief imagery, detailed lettering, and complex artistic elements that solid gold’s cost would make designers hesitate employing because mistakes or design changes would waste expensive materials, while silver core’s relative affordability permits artistic freedom and revision during design process that pure gold would constrain through economic pressure to minimize material usage and design complexity.

Shop on AliExpress via link: wholesale-sterling-silver-jewelry

IOC Regulations: Official Medal Standards

The International Olympic Committee Olympic Charter Rule 70 establishes comprehensive medal specifications that host organizing committees must follow including minimum size of 60 millimeters diameter and 3 millimeters thickness though modern medals typically exceed these minimums at 85 millimeters diameter and 8-10 millimeters thickness, with regulations also requiring that gold and silver medals contain at least 92.5% silver base with gold medals plated in minimum six grams of pure gold creating standardized precious metal content across all Olympics regardless of host nation or organizing committee preferences.

The design requirements mandate that obverse (front) side must depict specific imagery including Greek goddess of victory Nike in foreground with Panathenaic stadium in background plus Olympic rings, while reverse side allows host cities creative freedom to incorporate cultural elements, Games-specific imagery, or artistic designs that reflect local heritage and Olympic values creating balance between universal Olympic identity and host nation cultural expression. The inscription requirements specify that medals must include official Olympics name, host city, year, and sport for which medal awarded creating permanent record on medal itself documenting specific achievement and historical context that makes each medal unique beyond just athlete name and event that external documentation provides.

The quality control standards that IOC imposes through independent testing of sample medals ensures compliance with precious metal content, dimensions, and durability requirements before allowing mass production for actual awards ceremonies, with testing including material composition analysis, dimensional verification, and stress testing for resistance to normal handling that medals experience during ownership. The minimum production quantities that organizing committees must manufacture exceeds actual medal awards by approximately 15-20% creating buffer for damaged medals, presentation ceremonies, museum displays, and potential ties requiring additional medals beyond initially calculated needs based on event schedules and historical tie frequency in various sports.

The authentication measures including unique serial numbers, official IOC hallmarks, and certificates of authenticity that accompany medals provide verification of genuineness protecting against counterfeits that valuable Olympic memorabilia market inevitably attracts, with recent Olympics employing increasingly sophisticated anti-counterfeiting measures including micro-engraving, special alloys, and security features that expert examination can verify but casual counterfeiters cannot easily replicate. The medal ownership transfer that IOC permits without restriction after presentation means athletes maintain complete control and can sell, gift, donate, or bequeath medals without IOC approval or oversight though some national Olympic committees or governments impose restrictions on medal sales within their jurisdictions reflecting different cultural attitudes about commercializing sporting achievements versus treating medals as personal property that athletes earned through competitive success.

Material Value Breakdown: The $750 Reality

The precise material value calculation for Olympic gold medals uses current precious metal spot prices with 550 grams sterling silver at approximately $1.15-1.35 per gram creating silver value of $632.50 to $742.50, plus 6 grams pure gold at approximately $65 per gram adding $390 of gold value, totaling approximately $1,022 to $1,132 in raw precious metals before considering the 7.5% copper content in sterling silver and manufacturing costs that complete medal production requires. The material value fluctuation with precious metal market prices means identical medals have different intrinsic worth depending on when valued, with gold price volatility particularly affecting valuations because even six grams becomes significant when gold trades at $80+ per gram versus $50 per gram that historical lows have touched making total material value ranging from approximately $700 at low precious metal prices to $1,200 when gold and silver peak.

The manufacturing costs adding approximately $200-500 per medal for design, molding, plating, finishing, and quality control creates total production cost between $900-1,600 per medal that host organizing committees pay for creating official Olympic awards, with economies of scale reducing per-unit costs when producing thousands of medals versus small batches where setup costs and quality control expenses represent larger percentage of total production expense. The storage, presentation, and ceremony costs adding additional expenses for secure storage before Games, ribbon lanyards, presentation boxes, security during transport to venues, and ceremonial presentation logistics create complete medal program costs that Olympic organizing committees must budget as part of overall Games expenditure that typically represents tiny fraction of multi-billion dollar Olympic budgets but requires careful planning and execution ensuring medals arrive safely at correct venues for precise timing of victory ceremonies.

The comparison to jewelry market values where similar precious metal content and craftsmanship would cost consumers approximately $800-1,200 for custom sterling silver piece with gold plating demonstrates that Olympic medals’ material and production costs align reasonably with commercial jewelry despite medals’ unique designs and limited production creating scarcity that jewelry market doesn’t typically feature for mass-produced items. The recycling value that precious metal dealers might pay for Olympic medals based solely on metal content would approximate spot prices minus processing costs creating offers of perhaps $600-900 for melting down medals into raw materials, though obviously no athlete would accept this when auction market pays tens of thousands or more for medals with historical significance and provenance that material composition cannot capture or represent through economic value alone.

Market Value vs Intrinsic Worth: The $40,000 Gap

The astronomical gap between Olympic gold medals’ $700-850 material worth and $20,000-100,000 typical auction prices demonstrates how historical significance, athletic achievement, cultural meaning, and emotional resonance create valuations completely detached from physical material costs, with this phenomenon particularly pronounced for Olympic medals where symbolic value as ultimate sporting achievement combined with limited supply, global recognition, and personal stories creates perfect conditions for market values exceeding intrinsic worth by factors of 25 to 100 or more depending on specific medal’s history and associated athlete’s fame.

The factors determining individual medal auction values include athlete fame and achievement where household names like Jesse Owens, Mark Spitz, or Usain Bolt command premium prices versus unknown athletes whose medals sell for lower though still substantial amounts, historical significance where medals from politically or culturally important Olympics like 1936 Berlin, 1968 Mexico City, or 1980 Moscow carry added value beyond individual athletic achievement, sport popularity where track and field or swimming medals often outperform more obscure sports in auction market despite equivalent athletic difficulty, and personal narrative where compelling stories about athlete’s journey, obstacles overcome, or medal ceremony moments create emotional connections that buyers pay premiums acquiring beyond mere metal and achievement.

The authentication requirements for Olympic medal auctions demand provenance documentation proving medal legitimacy and ownership chain from athlete through any intermediate owners to current seller, with reputable auction houses requiring certificates of authenticity, photographic documentation of athlete with medal, and sometimes DNA or other forensic evidence linking specific medal to athlete’s participation before accepting consignment preventing fraud that valuable memorabilia market attracts from unscrupulous sellers attempting to profit from counterfeits or medals of dubious origin. The buyer motivations ranging from serious collectors building comprehensive Olympic memorabilia collections to wealthy sports fans wanting tangible connection to favorite athletes or historic moments, with some purchases representing investment strategies betting on continued appreciation of rare sporting memorabilia that limited supply and growing global wealth should support through increasing demand from collectors worldwide competing for finite number of authentic Olympic medals that athletes occasionally sell.

The ethical debates about athletes selling Olympic medals that some view as dishonoring achievement and betraying national pride versus others defending as legitimate exercise of personal property rights over medals that athletes earned through years of sacrifice and have absolute right to dispose of as they choose creates ongoing controversy that cultural attitudes, national traditions, and personal financial circumstances all inform differently across societies and individual situations. The financial necessity sales where athletes facing medical bills, business failures, or other economic hardships sell medals to raise needed funds generate sympathy and understanding even from critics who disapprove of selling medals purely for profit or collecting purposes, with Jesse Owens selling his 1936 medals in 1970s to support family after business ventures failed representing type of desperation sale that even traditionalists typically accept as understandable given circumstances even while lamenting that athletes might face such situations requiring medal sales for basic financial survival.

Shop on AliExpress via link: wholesale-sports-memorabilia-display

The Most Expensive Olympic Medals Ever Sold

The verified record for most expensive Olympic medal sale belongs to Jesse Owens’ 1936 Berlin Olympics gold medal purchased for $1,466,574 in December 2013 by billionaire Ron Burkle on behalf of his son though the medal eventually returned to Owens’ family through complicated arrangement demonstrating extreme prices that historically significant medals command when factors align perfectly creating legendary athlete, pivotal historical moment, and compelling narrative that transcends normal sporting achievement becoming cultural touchstone that generations remember and value.

The Wladimir Klitschko 1996 Atlanta Olympics gold medal for super heavyweight boxing sold for $1 million in March 2012 with proceeds donated to Ukrainian children’s charity, with high price reflecting both Klitschko’s subsequent fame as long-reigning heavyweight boxing champion and Ukrainian patriotism supporting charitable cause that buyers appreciated beyond mere medal acquisition creating auction dynamic where social good and national pride elevated bidding beyond purely collectible value. The Mark Wells 1980 Lake Placid Olympics hockey gold medal from famous “Miracle on Ice” victory sold for $310,700 in 2010 demonstrating that team sport medals from legendary accomplishments command substantial prices even when individual athletes might not achieve Owens-level fame, with this medal’s value stemming from team achievement and cultural moment that transcended individual performance creating lasting impact on American sporting consciousness.

The Anthony Ervin 2000 Sydney Olympics gold medal for 50-meter freestyle swimming sold for $17,101 in 2004 with proceeds donated to tsunami relief efforts represents more typical pricing for recent Olympic gold medals from less historically significant Olympics and athletes without household name recognition, though even this amount demonstrates how market values exceed material worth by factors of 20 or more. The various Olympic medals selling at auction for $15,000-50,000 representing normal range for authentic Olympic gold medals from reasonably recent Games without extraordinary historical significance or attached to legendary athletes shows consistent premium over material worth though not approaching record prices that unique circumstances create for truly exceptional medals combining multiple value factors simultaneously.

The comparison to other sporting memorabilia where Super Bowl rings, World Series trophies, and FIFA World Cup medals command similar price ranges demonstrates that Olympic medals while perhaps most globally recognized sporting prizes face comparable competition from region-specific sports whose fans bid aggressively for memorabilia despite more limited international appeal that Olympics’ universal recognition provides. The authentication services and auction houses specializing in Olympic memorabilia including Heritage Auctions, SCP Auctions, and Christie’s employ experts verifying medal authenticity through material analysis, historical documentation, and provenance research preventing fraud that high values inevitably attract from counterfeiters attempting to profit from collectors willing to pay substantial sums for rare sporting artifacts.

Cultural and Historical Factors Affecting Value

The cultural significance that specific Olympics acquire through historical circumstances dramatically affects associated medals’ market values, with 1936 Berlin Olympics representing perhaps most valued Games due to Nazi Germany context and Jesse Owens’ triumph over Hitler’s Aryan supremacy ideology creating politically and culturally charged moment that transcended athletics becoming powerful symbol of racial equality and human dignity that resonates across generations making medals from these Games particularly valuable regardless of sport or athlete fame.

The 1968 Mexico City Olympics acquiring special historical significance through Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ Black Power salute during medal ceremony created indelible image representing civil rights struggle that makes medals from these Games valuable beyond typical Olympics, with this Games also notable for high-altitude performances producing world records that stood for decades in some events adding athletic significance to cultural and political importance. The 1980 Moscow Olympics boycotted by United States and allies plus 1984 Los Angeles Olympics boycotted by Soviet bloc creating Cold War tension Olympics where medals symbolized geopolitical conflict beyond mere athletic competition makes these Games’ medals historically significant for political history that sporting achievement alone wouldn’t generate.

The athlete nationality affecting medal values in country-specific auction markets where home nation collectors pay premiums for medals won by compatriots versus international buyers who might value global stars over local heroes, with this dynamic creating interesting pricing variations where Scandinavian winter sports medals might command higher prices in Nordic countries than elsewhere while American track and field medals potentially bring premium prices in United States market. The sport prestige hierarchy where track and field, swimming, and gymnastics generally command higher prices than more obscure Olympic sports reflects global sports popularity and media coverage creating familiarity and emotional investment that mainstream sports enjoy over specialized activities that smaller audiences follow despite equivalent athletic difficulty and Olympic legitimacy.

The gender disparities in medal values where men’s medals historically sold for higher prices than comparable women’s medals from same Olympics reflects broader societal issues about women’s sports recognition and compensation, though this gap narrowing as women’s athletics gains prominence and cultural attitudes evolve toward greater gender equality in sports valuation and recognition. The Paralympic medals beginning to command respectable auction prices as Paralympic movement gains visibility and recognition demonstrates how cultural awareness and appreciation creates market value where previously little existed, with Paralympic champions’ inspiring stories and remarkable athletic achievements finally receiving commercial recognition that Olympic medals long enjoyed.

Manufacturing Process: How Medals Are Made

The Olympic medal manufacturing begins with design competition where International Olympic Committee and host organizing committee solicit proposals from artists and designers, with selected design then refined through iterative process ensuring artistic vision, technical feasibility, IOC regulations compliance, and cultural appropriateness all align before committing to final design that will appear on potentially thousands of medals representing Games’ official artistic statement.

The master model creation using three-dimensional computer modeling or traditional clay sculpting produces exact template that subsequent medals will replicate, with modern Olympics increasingly using digital design allowing precise control and modification before cutting steel dies that mass production requires, versus historical handcrafted master models where artistic skill and hours of manual labor created one-off originals that die-cutting machines then reproduced for actual medal production. The die creation using computer numerical control machining or traditional hand-engraving cuts reverse impression of final medal design into hardened steel blocks that striking presses will use for stamping medal blanks into finished products, with typical Olympic medal requiring multiple dies for different design elements that combine producing complete obverse and reverse imagery through sequential striking or single massive press operation depending on equipment and complexity.

The blank preparation beginning with casting or rolling sterling silver into proper thickness discs then machining to exact diameter and weight specifications creates foundation that plating and striking will transform into finished medals, with quality control at this stage ensuring all blanks meet weight, dimension, and composition standards before expensive striking and plating processes commence that rejecting defective blanks after processing would waste through ruining nearly complete medals. The striking process using massive hydraulic presses applying hundreds of tons of force drives medal blank between dies imprinting obverse and reverse designs simultaneously through metal deformation that creates bas-relief imagery, with typical medal requiring multiple strikes achieving desired depth and detail that single pressing might not fully develop particularly for intricate designs with fine details or varying relief depths.

The gold plating application using electroplating process submerges struck silver medals in gold salt solution while electrical current deposits pure gold atoms onto all exposed silver surfaces, with duration, current strength, and solution concentration carefully controlled achieving specified minimum six grams gold coverage that IOC regulations mandate with typical plating lasting several hours ensuring even coating thickness across medal’s complex three-dimensional surface. The quality inspection examining each finished medal for defects, measuring gold plating thickness through x-ray fluorescence or destructive testing of sample medals, and verifying weight and dimensions ensures all medals meet specifications before accepting for Games use, with rejection rates typically 2-5% requiring reprocessing or scrapping creating waste that manufacturing cost calculations must account for in total program expense.

The final finishing including polishing, protective coating application, ribbon attachment, and serial number engraving prepares medals for presentation, with packaging in official cases and preparation of certificates of authenticity completing production process that transforms raw silver and gold into symbols of Olympic achievement that athletes will treasure throughout lives. The manufacturing timeline typically requiring 18-24 months from design selection through final delivery creates long lead time that organizing committees must plan for ensuring medals available for first medal ceremonies that often occur just days into Olympics when early events conclude creating urgency that manufacturing schedule must accommodate through careful planning and quality assurance that prevents last-minute crisis from production problems or delivery delays.

Shop on AliExpress via link: wholesale-medal-display-case

Paralympic Medals: Equal Composition, Unique Features

The Paralympic medals maintaining identical composition, weight, dimensions, and precious metal content to Olympic medals demonstrates International Paralympic Committee commitment to parity between Olympic and Paralympic achievements, with Paralympic gold medals using same sterling silver core with six grams gold plating creating equivalent material value and prestige that distinguishes Paralympic medals from historical treatment of disability athletics as lesser category deserving inferior recognition compared to able-bodied competition that modern Paralympic movement successfully challenged through asserting equal athletic merit and achievement worthy of equivalent honors.

The unique accessibility features that Paralympic medals incorporate including small steel balls inside medal that rattle when shaken allow visually impaired athletes to identify medal color through sound, with gold medals containing three rattling balls, silver medals two balls, and bronze medals one ball creating tactile and auditory differentiation that visual medal color provides for sighted athletes but blind or visually impaired Paralympians cannot access without alternative identification method. The Braille inscriptions on recent Paralympic medals provide additional accessibility allowing visually impaired athletes reading medal details through touch rather than relying on sighted assistance for information that able-bodied athletes can read visually, with this accommodation demonstrating thoughtful design ensuring Paralympic medals serve all athletes regardless of visual ability.

The Paralympic symbol consisting of three agitos (from Latin meaning “I move”) representing mind, body, and spirit appears on Paralympic medals similar to how Olympic rings identify Olympic medals, with this distinct imagery creating separate identity for Paralympic movement while maintaining parallel prestige and recognition that Paralympic champions deserve equally to Olympic counterparts despite historical marginalization of disability sports that modern Paralympics successfully overcame through competitive excellence and cultural advocacy changing attitudes about disability athletics from charity activity to elite sport deserving mainstream recognition and commercial support.

The market value for Paralympic medals beginning to establish meaningful auction prices reflects growing Paralympic awareness and appreciation, with recent Paralympic champion medals selling for several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars demonstrating that collectors recognize Paralympic achievement value beyond material composition though not yet approaching Olympic medal auction records that century of Olympic cultural dominance created through superior media coverage and public familiarity that Paralympics only recently began receiving at scales approaching Olympic visibility.

Controversial Medal Sales: Athletes Who Sold

The Jesse Owens medal sales in 1970s to support family after business ventures failed represented financially desperate transaction that even critics sympathized with given circumstances, with Owens later expressing regret about selling medals though economic necessity had forced decision that pride alone might have rejected if financial security permitted keeping symbols of greatest athletic achievements for family legacy rather than commercial transaction providing needed cash that desperation made seemingly only option available.

The Vladimir Klitschko donation of one million dollar medal sale proceeds to Ukrainian children’s charity transformed potential controversy about Olympic champion selling medal into feel-good story about athlete using medal value for public good rather than personal enrichment, with this charitable purpose deflecting criticism that might otherwise have questioned appropriateness of Olympic champion commercializing achievement for profit versus using sale to generate funds supporting worthy cause that broader social benefit justified through helping disadvantaged children.

The Anthony Ervin tsunami relief donation from medal sale similarly created positive narrative where athlete selflessly contributed to disaster recovery through monetizing personal achievement for humanitarian purpose rather than financial gain, with these charitable sales generally receiving public approval even from traditionalists who might oppose selling medals purely for profit or collectors’ purposes that private benefit motivates rather than public good that charitable donations serve.

The various athletes selling medals through financial hardship including medical bills, business failures, or family emergencies create sympathetic cases where critics acknowledge that athletes facing genuine financial crisis shouldn’t sacrifice families’ welfare to preserve symbolic objects regardless of cultural significance that medals represent, with this pragmatic recognition that survival and family support trump symbolic gestures reflecting mature understanding that while medals carry meaning, their value ultimately should serve athletes and families who earned them through competitive sacrifice rather than becoming burdens that financial pride prevents monetizing when circumstances demand.

The controversy around athletes selling medals for profit or collecting without financial necessity divides opinion between traditionalists arguing medals should remain family heirlooms representing achievement that commercialization dishonors versus modernists defending absolute property rights that athletes earned medals through competitive success giving complete discretion about retention or sale without moral judgment that others shouldn’t impose on personal decisions about property disposition. The cultural variations where some nations legally prohibit or strongly discourage medal sales through national heritage laws or social pressure versus others accepting sales as normal exercise of property rights demonstrates different societal attitudes about individual freedom versus collective interests in preserving national sporting heritage that medals represent beyond personal athletic achievement.

Legal Status: Can Athletes Sell Their Medals?

The legal framework governing Olympic medal ownership and sales varies dramatically by nation with United States allowing unrestricted sales based on First Amendment protections of personal property rights and commercial speech preventing government prohibition of medal sales that athletes choose making voluntarily, while other nations including Russia and Cuba impose restrictions through cultural heritage laws treating Olympic medals as state property or protected national artifacts that private commercial transactions shouldn’t involve regardless of athlete ownership during their lifetimes.

The International Olympic Committee maintaining no ownership rights over medals after presentation to athletes means IOC cannot legally prevent sales even if institutionally opposed, with medals becoming unrestricted personal property upon award giving athletes complete legal control over retention, sale, donation, destruction, or any other disposition without requiring IOC permission or notification that property ownership normally implies though some athletes might feel moral obligations to preserve medals as heritage items despite lacking legal requirements compelling retention.

The auction house policies requiring authentication and provenance documentation before accepting Olympic medals for sale prevents fraud through verifying medals’ legitimacy and establishing clear ownership chain from athlete to current seller, with reputable houses refusing medals lacking proper documentation even when authentic because unclear ownership creates legal liability risks that professional auction operations cannot accept regardless of potential commission revenue that sales would generate. The buyer protections through warranties and return policies that established auction houses provide give collectors confidence purchasing expensive medals knowing that discovery of fraud or ownership disputes would allow recourse through returning medals and obtaining refunds versus private sales where caveat emptor principles might leave buyers holding worthless counterfeits or stolen medals that legal owners could reclaim through court action.

The taxation of medal sales as capital gains or collectibles depending on jurisdiction creates significant tax liability that athletes must consider when selling, with United States treating medals as collectibles taxed at twenty-eight percent maximum rate versus ordinary income tax rates that could reach thirty-seven percent for highest earners though lower than some European nations where combined national and local taxes on collectibles sales can exceed fifty percent creating substantial tax bills that sale proceeds must cover reducing net athlete benefit from transactions.

The ethical debates beyond legal status about whether athletes should sell medals that represent not just personal achievement but national investment through training facilities, coaching, and financial support that Olympic programs provide creates argument that athletes owe nations or sporting federations moral obligation not to commercialize medals even when legal rights permit sales, though this position struggles against countervailing view that athletes’ years of sacrifice and dedication earned medals making them absolutely personal property that no one else can claim moral authority over despite public investment in Olympic sports infrastructure that contributed to athlete success.

The Psychology of Medal Value: Why Symbolism Trumps Material

The fundamental psychological principle that symbolic meaning and emotional significance create value completely independent of material composition explains why Olympic gold medals worth $750 in metals sell for tens of thousands or millions at auction, with this phenomenon extending far beyond sports into art, historical artifacts, religious relics, and cultural objects where meaning rather than material determines worth that markets assign through collector willingness paying premiums for symbolic significance that purely material valuation cannot capture or explain adequately.

The achievement symbolism that Olympic medals represent as ultimate sporting recognition from global competition involving billions of viewers and years of preparation creates psychological value that transcends physical object through representing human peak performance, dedication, sacrifice, and excellence that societies universally admire and celebrate regardless of specific sports interest or national affiliation. The scarcity principle where Olympic gold medals’ limited quantity from just thousands awarded quadrennially across all sports and nations creates supply constraint that collector demand exceeds dramatically particularly for medals from famous athletes or historically significant Olympics that availability proves even more restricted through natural attrition as medals become lost, destroyed, or permanently retained by athletes and families.

The vicarious achievement that collectors experience through owning Olympic medals allows participation in sporting glory through proxy possession of tangible symbols representing athletic excellence that buyers themselves might admire but cannot achieve personally, with this psychological dynamic driving willingness to pay substantial sums for connection to achievement and athletes that ownership provides beyond mere material object acquisition. The legacy preservation motivation where collectors view themselves as heritage custodians protecting important historical artifacts for future generations creates altruistic self-conception that premium prices become justified protecting medals from loss or destruction that family retention might not guarantee across generations where descendants might lack appreciation or financial need might force poorly considered sales to unscrupulous buyers.

The nostalgia and emotional connection that Olympic moments create through childhood memories of watching historic performances or national pride from compatriot victories makes medals from those specific Olympics or athletes carry personal emotional significance that rational economic calculation cannot explain but psychological attachment fully justifies for individuals willing paying premiums reliving important personal or cultural memories through tangible objects representing those emotionally charged moments. The investment psychology where some buyers view rare Olympic medals as alternative assets that should appreciate over time as wealth grows globally and collector base expands creates financial motivation supplementing or replacing pure collecting interest, with track record of major Olympic medal sales showing consistent appreciation suggesting that investment thesis has validity though illiquidity and authentication concerns create risks that traditional investments avoid.

Unique Medal Designs Through Olympic History

The artistic evolution of Olympic medal designs from simple classical imagery celebrating Greek heritage toward culturally diverse expressions reflecting host nations’ identities demonstrates how Olympic medals transformed from generic sporting prizes into artistic statements that Games’ visual identity creates through thoughtful design incorporating local culture, artistic traditions, and contemporary aesthetics that make each Olympics’ medals distinct collector items beyond standardized awards that identical designs across Games would create.

The 2008 Beijing Olympics medals incorporating jade rings represented first Olympic medals embedding precious stones creating additional material value and cultural significance because jade holds special meaning in Chinese culture as symbol of virtue, nobility, and prosperity making its inclusion in medal design communicating Chinese values while adding approximately $200-300 additional material worth beyond gold and silver content. The 2016 Rio Olympics medals using recycled materials including gold from electronic waste and silver from recycled X-ray plates demonstrated environmental consciousness while maintaining required precious metal content, with this sustainability focus reflecting contemporary concerns about resource conservation that traditional mining for medal materials doesn’t address though criticism questioned whether using virgin materials for limited-production high-value items like Olympic medals represented significant environmental impact worth addressing given much larger industrial and consumer electronics sectors creating actual electronic waste crisis.

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics medals continuing recycled materials theme collecting approximately 78,985 tons of electronics waste from Japanese population donations producing required gold, silver, and bronze through urban mining that public participation campaign supported demonstrating grassroots Olympic involvement beyond mere spectating that material contribution created through citizens donating old devices knowing their precious metals would become Olympic medals. The Paralympic medals featuring Japanese traditional fan motifs with different textures allowing tactile identification combined with internal rattling balls created most accessible Paralympic medals ever designed demonstrating how universal design principles can enhance functionality for athletes with disabilities while creating aesthetically interesting pieces that able-bodied athletes also appreciate.

The various Olympic medals through history featuring unique elements including 1992 Barcelona medals with asymmetric wave design departing from traditional circular format, 2000 Sydney medals with curved profile creating three-dimensional form, and 2012 London medals as heaviest ever produced at 400 grams before subsequent Games exceeded that weight approaching modern 556-gram standard demonstrate ongoing innovation and experimentation that prevents Olympic medals becoming stale repetitive designs instead maintaining freshness and contemporary relevance through artistic evolution reflecting changing design sensibilities and cultural values.

Shop on AliExpress via link: wholesale-collectible-coins-medals

Environmental Sustainability: Recycled Gold and Silver

The environmental impact of Olympic medal production using virgin mined precious metals creates carbon footprint and ecological damage from mining operations that recent Olympics have addressed through urban mining initiatives collecting electronic waste for medal production, with Tokyo 2020 pioneering large-scale implementation though Rio 2016 initiated concept demonstrating feasibility and public appeal of sustainable sourcing that environmental consciousness increasingly demands from large events including Olympics whose global platform creates responsibility for modeling environmental stewardship that billions of viewers observe.

The electronic waste problem where discarded phones, computers, and appliances contain significant precious metal content that traditional disposal wastes through landfilling or inefficient recycling creates opportunity for recovering gold, silver, and copper that Olympic medals require without environmental damage from new mining operations, with typical smartphone containing approximately 0.034 grams of gold, 0.34 grams silver, plus various other metals making large-scale collection yielding sufficient precious metals for Olympic medal production when millions of devices aggregated providing necessary tonnage.

The carbon footprint comparison between virgin mined precious metals and recycled materials shows recycled gold producing approximately 99% less carbon emissions than newly mined equivalent because mining requires earth moving, ore processing, chemical refining, and transportation creating massive energy consumption while recycling uses significantly less energy and produces minimal new environmental damage beyond electricity for smelting and refining operations. The Tokyo 2020 campaign collecting approximately 78,985 tons of electronic devices from 1,300 municipalities across Japan produced 32 kilograms gold, 3,500 kilograms silver, and 2,200 kilograms bronze sufficient for all 5,000 medals that Games required demonstrating that urban mining can satisfy Olympic precious metal needs without any traditional mining impact.

The public engagement that recycling campaigns create through inviting citizen participation in Olympic medal production develops emotional connection and environmental awareness that purchasing recycled materials from commercial suppliers wouldn’t generate, with participants feeling personal investment in Games knowing their donated devices contributed to medals that winning athletes will cherish representing not just individual achievement but collective effort including ordinary citizens who rarely consider themselves Olympic participants despite making tangible contributions through material donations.

The future implications for precious metal sourcing more broadly as urban mining technology improves and electronic waste volumes continue growing suggests that Olympic precedent might accelerate industry transition from virgin mining toward recycling as primary precious metal source reducing environmental damage while meeting industrial and decorative demand that traditional mining currently satisfies despite known environmental and social costs that sustainable alternatives could avoid.

The Future of Olympic Medals: What's Next?

The potential elimination of precious metals entirely from Olympic medals has occasionally been proposed by reformers arguing that symbolism rather than material creates meaning making gold, silver, and bronze unnecessary expensive anachronisms that cheaper alternatives could replace while maintaining three-tier award system through different materials or colors that achievement hierarchy communicates without requiring precious metals, though this radical proposal faces overwhelming traditional resistance from Olympic movement stakeholders who view precious metal medals as sacred tradition that identity and prestige both depend on maintaining regardless of economic arguments favoring alternatives.

The augmented reality and digital enhancements that future medals might incorporate through NFC chips, QR codes, or electronic displays creating interactive experiences where scanning medal provides access to performance videos, athlete information, or commemorative content represents technological evolution that physical medals could embrace while maintaining traditional form and precious metal composition adding digital layer without replacing tangible award that Olympic tradition demands.

The blockchain authentication using distributed ledger technology to create unforgeable digital certificates of authenticity linked to physical medals could eliminate counterfeiting concerns that valuable Olympic memorabilia market faces, with each medal receiving unique blockchain identifier that ownership transfers would update creating permanent transparent record of provenance from initial athlete award through any subsequent sales or donations that collectors and auction houses could verify instantaneously without extensive research or expert authentication that current systems require.

The environmental sustainability improvements through increased recycled content, reduced precious metal quantities, or alternative sustainable materials that equivalent prestige provides represents likely evolutionary direction as environmental concerns intensify and urban mining infrastructure develops making recycled precious metals more accessible and cost-effective than current practices where some recycling occurs but virgin mining still dominates precious metal supply chains that sustainability advocates increasingly challenge through demonstrating viable alternatives.

The personalization opportunities where athletes could customize medals with engravings, gem settings, or other additions transforming generic medals into unique personal artifacts represents potential evolution that current standardization prevents but technology and cultural shifts toward individual expression might enable through allowing modifications after presentation while maintaining official design and composition that ceremony requires but subsequent personalization permits as athletes’ personal property to modify as desired.

Conclusion: The True Value of Olympic Gold

The comprehensive examination of Olympic gold medals’ composition, history, value, and significance reveals that physical material worth of $750 proves completely irrelevant to actual value that symbolic meaning, cultural significance, historical context, and personal achievement create through transforming simple precious metal objects into priceless artifacts representing human excellence, dedication, sacrifice, and peak performance that billions worldwide recognize and celebrate as ultimate sporting achievement regardless of awareness about material composition or manufacturing costs.

Your understanding of Olympic medals should transform from viewing them as primarily valuable for gold content toward recognizing that meaning rather than material determines worth, with this principle extending far beyond Olympics into art, history, religion, and culture where symbolic significance creates valuations that material composition cannot explain but psychological attachment, emotional resonance, and cultural meaning fully justify through connecting tangible objects to intangible values that human societies treasure above mere physical resources.

Begin appreciating Olympic medals not for precious metal content but for representing peak human achievement through years of dedication, sacrifice, and relentless pursuit of excellence that most people admire but few actually accomplish, with each medal telling unique story of athlete’s journey through adversity, triumph, disappointment, and ultimately success that gold, silver, and bronze symbolize through universal recognition transcending language, nationality, and culture.

Frequently Asked Questions - COMPLETE DETAILED ANSWERS

Question 1: Are Olympic gold medals actually made of solid gold?

Answer 1: Olympic gold medals do not contain solid gold construction but rather consist of sterling silver core weighing minimum 550 grams composed of 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper alloy that provides structural strength and durability that pure silver’s softness would lack, with this substantial silver base receiving coating of minimum six grams pure gold applied through electroplating process creating thin gold layer typically measuring 6-8 micrometers thickness that covers entire medal surface providing authentic gold appearance and sufficient precious metal content to justify “gold medal” designation while avoiding solid gold’s prohibitive cost that economic reality forced abandoning after 1912 Stockholm Olympics awarded last solid gold medals before International Olympic Committee regulations formalized gold-plated silver standard that has persisted for over century with only minor variations in plating thickness and base metal purity that different host cities employ.

The transition from solid gold to gold-plated construction occurring after 1912 reflected not sudden arbitrary policy change but gradual recognition that Olympic growth from several hundred participating athletes to thousands made solid precious metal medals economically impractical, with 1912 Stockholm Games representing final gasp of attempting to maintain solid gold tradition before expanding athlete numbers and host city financial constraints forced permanent change to more economically sustainable medal composition. The 1912 solid gold medals using approximately 24 grams of pure gold created material value around $1,500 at current gold prices compared to modern gold-plated medals containing just six grams worth approximately $390 of gold plus $650-750 sterling silver totaling under $1,200 combined precious metal value demonstrating significant cost savings that plating achieves while maintaining genuine gold and silver content that tradition and prestige both require.

The electroplating process that applies gold coating to silver medals uses electrochemical method where electrical current passes through gold salt solution with medal acting as cathode attracting positively charged gold ions that bond to silver surface creating uniform coating controlled by current strength, duration, and solution concentration, with typical plating operation requiring several hours achieving specified minimum six grams gold thickness that International Olympic Committee regulations mandate for official medals. The plating thickness of 6-8 micrometers representing approximately 0.006-0.008 millimeters seems incredibly thin measuring just fraction of human hair width yet proves sufficient creating durable gold finish that resists normal wear during decades of ownership when properly cared for through avoiding harsh chemicals, excessive polishing, and environmental extremes that might accelerate gold layer deterioration.

The visual appearance of gold-plated medals proving indistinguishable from hypothetical solid gold equivalents to casual observation means most athletes and viewers never realize medals aren’t solid gold unless specifically informed about composition, with this aesthetic equivalence combined with genuine precious metal content making plated medals satisfy tradition and prestige requirements that pure symbolic medals without actual gold and silver could not achieve despite being functionally adequate for representing achievement. The regulation requiring minimum precious metal standards rather than permitting cheaper alternatives like bronze with gold finish or purely symbolic awards demonstrates International Olympic Committee understanding that tradition and perceived value require genuine gold and silver content even when economic efficiency might suggest otherwise, with minimum standards ensuring medals contain real value beyond purely symbolic tokens while pragmatic plating rather than solid construction allows Games financial sustainability that pure precious metal would threaten.

The historical evolution from ancient olive wreaths containing zero monetary value through early modern Games’ solid gold medals to current gold-plated silver standard demonstrates how Olympic traditions adapt to practical realities while maintaining symbolic continuity connecting contemporary Games to historical roots, with careful balance between honoring tradition through using precious metals and adapting to economic constraints through pragmatic composition changes showing institutional wisdom that symbolic power derives from meaning and cultural significance rather than specific material formulations that can evolve without diminishing achievement recognition that medals represent.

Question 2: What is the actual material value of an Olympic gold medal?

Answer 2: The precise material value calculation for contemporary Olympic gold medals uses current precious metal spot prices showing 550 grams sterling silver at approximately $1.15 to $1.35 per gram creating silver value between $632.50 and $742.50 depending on market fluctuations, plus six grams pure gold at approximately $65 per gram adding $390 gold value, with combined precious metal content totaling approximately $1,022 to $1,132 before considering the 7.5% copper content in sterling silver and manufacturing costs that complete medal production requires including design, die cutting, striking, plating, finishing, quality control, packaging, and presentation expenses that host organizing committees pay creating total production costs between $900 and $1,600 per medal.

The material value fluctuation with precious metal market prices means identical medals have different intrinsic worth depending on valuation timing, with gold price volatility particularly affecting calculations because even six grams becomes significant when gold trades at $80 or more per gram versus $50 per gram that historical lows touched making total material value ranging from approximately $700 at depressed precious metal prices to $1,200 or more when gold and silver markets peak through economic uncertainty, investment demand, or industrial consumption creating upward pricing pressure. The silver price proving generally more stable than gold with less dramatic fluctuations means that medal value variations stem primarily from gold price volatility though silver comprising 98.9% of medal weight by precious metal content means silver price movements do affect total value particularly during rare occasions when silver prices spike through industrial demand or investment speculation that periodic silver market rallies create before typically correcting downward toward long-term average ranges.

The manufacturing costs adding $200 to $500 per medal for complete production process from initial design through final presentation creates total per-medal expense that Olympic organizing committees budget as part of overall medal program costs, with economies of scale reducing per-unit expenses when producing thousands of medals simultaneously versus small batches where setup costs, die cutting expenses, and quality control overhead represent larger percentage of total production cost making mass production significantly more cost-effective than limited runs. The medal program budget typically representing tiny fraction of multi-billion dollar Olympic organizing budgets means that medal costs rarely create financial pressure despite involving genuine expenses for precious metals and manufacturing that total several million dollars for complete Summer Olympics medal production including gold, silver, and bronze medals plus extras for damaged pieces, presentation ceremonies, museum displays, and tie-breaking situations requiring additional medals beyond initially calculated quantities.

The comparison to commercial jewelry market where similar precious metal content and craftsmanship would cost consumers approximately $800 to $1,200 for custom sterling silver piece with gold plating demonstrates that Olympic medal material and production costs align reasonably with retail jewelry despite medals’ unique designs, limited production creating scarcity, and cultural significance that jewelry market doesn’t typically feature for mass-produced items. The artisan jewelry using comparable materials and hand-craftsmanship might actually cost more than Olympic medals on per-unit basis when considering design time, individual production attention, and retail markup that commercial jewelry requires versus Olympics’ manufacturing efficiency through mass production, specialized facilities, and elimination of retail distribution costs that direct government contracting with manufacturers avoids.

The recycling value that precious metal dealers might offer for Olympic medals based solely on metal content would approximate spot prices minus processing costs creating potential offers of perhaps $600 to $900 for melting down medals into raw silver and gold that refineries could resell or reprocess into new products, though obviously no athlete would rationally accept this when auction markets pay tens of thousands or more for medals with provenance and historical significance that material composition cannot capture through economic value alone. The theoretical recycling scenario demonstrates how dramatically symbolic and historical value exceeds intrinsic material worth that precious metal content provides, with 20 to 100 times multipliers or more separating material value from actual market prices that collectors willingly pay for authentic Olympic medals from notable athletes or historically significant Games.

The insurance valuations that athletes obtaining coverage for medal theft or damage must establish typically use auction comparables or professional appraisals creating insured values of $15,000 to $50,000 for typical recent Olympic gold medals versus $700 to $1,200 material worth, with insurance companies accepting these valuations because replacement value for athlete includes not just material but also intangible loss of irreplaceable achievement symbol that original medal represented making monetary compensation attempt at covering not just physical object but emotional and psychological loss that theft or destruction would create for athlete and family treasuring medal as heritage item beyond mere valuable possession.

Question 3: Why did the Olympics stop making solid gold medals?

Answer 3: The Olympic transition from solid gold to gold-plated silver medals after 1912 Stockholm Games stemmed from unavoidable economic mathematics where explosive athlete participation growth made maintaining solid precious metal awards financially unsustainable even for wealthy host nations, with calculations showing that 1912 Stockholm awarded 885 medals across all events while modern Summer Olympics distribute over 5,000 medals representing nearly six-fold increase that solid gold would make prohibitively expensive costing approximately $50 to $75 million in gold materials alone at current prices before manufacturing and presentation expenses. The Stockholm organizing committee’s final commitment to solid gold using approximately 24 grams per medal created material costs around $1,500 each in contemporary currency totaling over $1.3 million for gold medals alone when most host cities were spending equivalent of $50 to $100 million total for entire Olympics making medal costs representing more than one percent of total budgets creating financial pressure that subsequent Games could not sustain as athlete numbers continued growing through expanding sports, events, and participating nations.